The Secretary of Defense is on his way out. To my mind, Gates was excellent, although, as Walt notes, coming after Donald Rumsfeld could make anyone look good. Gates, more than any SecDef since the end of the Cold War, has pushed the real ‘transformation’ of DoD – toward restraint and limits.

Readers will recall Secretary Rumsfeld’s original use of that term meant a smaller, lighter force that could intervene rapidly and globally to force local decisions on America’s terms. Afghanistan 2001 originally seemed like a model of this, but the bog-down of the war on terrorism has frozen the ‘revolution in military affairs.’ Rather it is Gates who has pushed the real change – nudging the US, specifically Beltway think-tank elites like Brookings or the American Enterprise Institute, to realize that the US can no longer afford the expansive globocop role we have become accustomed to in the ‘unipolar moment.’ Besides Walt, Fred Kaplan has been excellent on this.

Whoever comes after Gates will have a difficult time continuing this. There is a strong predilection in the Pentagon and on Capitol Hill for defense spending. It looks patriotic and exciting. Cutting it can be easily demagogued as ‘imperiling our national defense in an era of terrorism’ or something like that. Pentagon weapons procurement is notorious for placing bits and pieces of defense production in as many congressional districts as possible. This gives everyone a an economic and ‘patriotic’ stake in voting yet more cash to DoD. And the Navy and Air Force are genuinely terrified of a much-reduced role if the future use of American force becomes mini-interventions like Libya or (what was supposed to) Afghanistan. Watch for those parts of the force to hype the China threat (although I do think China containment, with a US supporting role, is probably inevitable).

Finally, it is simply undeniable that Americans sorta like ‘empire.’ We like the fact that we can go anywhere in the world and command a level of respect, because we are citizens of the ‘indispensible nation.’ Everyone uses the dollar and pays attention to the intricacies of our politics. (In Africa last summer, I got questioned regularly on Obama). No, I’m not saying we are the European caricature of global-strutting imperialist. But you only need to watch American film (or worse, video games) to see how attractive the idea of a big, bad-a—US is to Americans. We love the narrative of American exceptionalism; remember that George W Bush said ‘God has a special mission for America,’ and he got re-elected despite the Iraq War. You don’t have to be Noam Chomsky to think this; just live outside the US for a few years to see how ‘the rest’ think about us.

So Gates’ value, in the end, was seeing that the US simply cannot afford the neocon-liberal hawk synthesis in which the US use of force is a regular response to global problems. Even if you think America should be globobcop, America’s finances force the obvious question of whether we can. Historians regularly tell us that rising debt and long foreign wars are the death-knell of empires. Cut we must, or face a truly devastating melt-down at some point. It will take time for Americans to digest this reality, and Gates, with his huge personal prestige, started this process.

I say that quite aware that I supported NATO force against Gaddafi. (I would defend that position by noting that I argued for a super-light air intervention to stop a massacre. Beyond that, Libyans must achieve ‘regime change’ on their own.) I also say this with some trepidation, because part of me does think that unipolarity backed by US force, has made the world safer and the global economy function more easily. I worry too what a ‘post-American’ world will look like, especially if authoritarian China plays a much bigger role. While no fan of ‘empire,’ I will agree that this is unnerving.

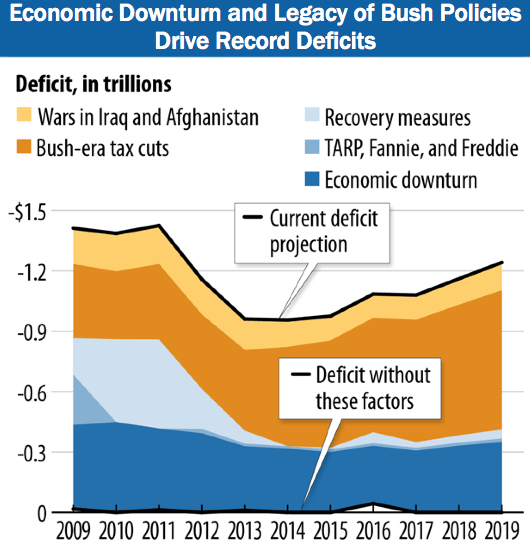

But the larger concern of overstretch is now so apparent that Gates’ retrenchment position can either be, a) a choice now, in which we slowly retrench in order to better accommodate America’s fiscal mess and do so in a professional, ‘graceful’ manner, or b) forced on us later, when when we are genuinely broke because we continue to borrow $1-2 trillion dollars a year. Even America can’t do that forever, and cuts are coming whether we want them or not.

The Korean case has really forced my thinking about this, because Korea’s security is obviously dependent on a US commitment. Any war here will be bloody and expensive, far worse than the US post-Cold War wars in the Middle East. Americans are genuinely nervous about getting chain-ganged into a long conflict here. China, which holds around 1/4 of all US T-bills, would have an obvious incentive to stop buying if US Forces in Korea were suddenly marching toward the Yalu. And I can think of few uses of US force more noble than helping a democracy against the world’s last, worst stalinist tyranny. But that shouldn’t blind us to the obvious. Gates himself said, “any future defense secretary who advises the president to again send a big American land army into Asia or into the Middle East or Africa should ‘have his head examined.’” That should be a wake-up call.

Hence I have argued repeatedly here, especially for Korean readers, that Korea needs to be far more aggressive in preparing its own defense and imaging an East Asian alliance structure beyond simply a US guarantee. Korea should finally end the tiresome, endless Dokdo dispute with Japan, so that real joint decision-making on vastly greater issues like NK or China’s rise can begin. Korea should be looking further afield to other Asian democracies like India, Australia, and the Philippines. These are no substitute for the US of course, and the US isn’t simply going to leave tomorrow or next year. But the US will have to be further and further ‘over the horizon’ in the medium-term, barring some major turn-around of the US fiscus. Korea has the money and talent to fill in this gap, but first the recognition of US limits, pushed by no less than the US secretary of defense, needs to sink in – not just in Seoul, but in the whole US establishment in Korea, and in the Beltway think-tank industrial complex. I hope I am wrong…