Part 2 is here.

The following is a brief analysis of what NK will ‘learn’ from Arab Spring. The good people at the Korea National Defense University asked for a quick, non-jargony write-up. I have previously written for KNDU’s Research in National Security Affairs (RINSA) notes here (no. 70), about NK’s shelling of Yeonpyeong island last year. Northeast Asia security wonks would like RINSA.

Comments would be appreciated, as this will be published in the next few weeks. For my previous writing on Arab Spring, go here.

ABSTRACT

NK will draw six lessons from Arab Spring: 1. Quash protest as quickly as possible. 2. Give the military everything it wants. 3. Return to post-colonial ideology. 4. Find new nuclear proliferation clients. 5. Cleave to China, as the moral cover of fellow autocracies fades. 6. Do not give up the nuclear weapons – ever. In short – dig in your heel, clamp down harder, don’t change.

The Arab Spring revolts present a frightening prospect to any dictatorship. As the world’s most orwellian and repressive – Human Rights Watch has given NK its lowest score for almost forty consecutive years – the DPRK will clearly draw lessons from these events. Six ‘tips’ for NK stand out:

1. Quash protest as quickly as possible. Precisely because the Arab revolts drag on and on, they have held world attention long enough to force a major debate on the premises of Western policy in the Middle East (ME). The longer revolts continue, the harder it becomes for outsiders to ignore them and the louder calls for external intervention become. This ‘CNN effect’ – in which a steady stream of horrific images from conflict or other catastrophe raises hard, increasingly unavoidable moral questions about external intervention – precipitated US pressure on Mubarak, the French turn-around on Tunisia, NATO bombing in Libya, and a possible future intervention in Syria. The best way to keep outsiders out is absolute control. Tiananmen Square (1989), Burma’s Saffron Revolution (2007) and Iran’s Green Revolution (2009) were definitively crushed, while Mubarak tried to negotiate. Chinese overreaction to the proposed ‘jasmine revolution’ is the likely NK response to any civil protest, only yet harsher.

2. Give the military everything it wants. ‘People power’ does not undo dictatorships, splits in the regime, particularly the security services, do. Mubarak lost when the military split over the repression; Yemen and Libya’s rebels have strengthened as the militaries fractured. Son-gun was prescient in its blatant effort to buy off the KPA, even as it bankrupts the DRPK budget.

3. Return to post-colonial ideology. The growing global normative acceptance of the ‘responsibility to protect’ (R2P), the intellectual justification for external human rights-motivated intervention, narrows NK’s ideological space. R2P, for which even China and Russia voted in the UN, raises the ‘audience costs’ of the NK dictatorship. It posits that a legitimate government must meet a minimum threshold of good behavior toward its own people to preclude external intervention: some governments are so bad, they forfeit the right to rule. To date this has been used to justify interventions in Libya, Kosovo, Bosnia, and Somalia; it also impacted the debate on Darfur, Ivory Coast’s recent internal conflict, and a possible future intervention in Syria. This is an important breach of the long-standing norm of mutual, sovereign non-interference, behind which NK and most dictatorships hide.

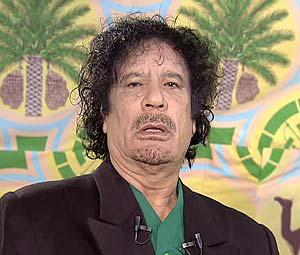

No case more clearly meets the R2P benchmark than NK with its man-made famines, concentration camps, and extreme privation. The DPRK needs an intellectual response to this challenge, and anti-colonial nationalism is a good choice. Decolonization stirs strong feelings in the global South, the region most likely to confront R2P-motivated interventions. Qaddafi portrays the NATO bombing campaign as Western neocolonialism, with good effect in the African Union, which has repeatedly called for a NATO halt. A vigorous argument to global public opinion that SK is a US puppet bent on globalist exploitation of the peninsula would be a persuasive postcolonial counter to the ‘human rights imperialism’ critics fear in R2P. Further, ideological committed security forces, like Iran’s Basij, are less likely to split with the regime, so propagandizing the KPA complements ‘tip’ 2 above.