Last year in January, I made some predictions on Asian security. It is always useful to look back at how one did. I did ok, but one might criticize me that I predicted too many things would not happen. That predicts the lack of change, which is easier than predicting proactive change. That is true.

But prediction is one of the great goals of the social sciences. Indeed it is our hardest chore, and no matter how much we read, data we collect, or theories we propound, we still don’t seem to do much better than the ‘random walk’ theory. Depressing, but nonetheless worth the effort. So here is a quick review of my record. (For a nice collection of the worst world politics predictions from 2010, try here; thankfully none of mine are as eye-rollingly bad as them.) Here is a nice run-down from CFR on the big (East) Asia events of 2010. Note the differences from mine below.

My review of my 2010 Korea predictions will go up on Thursday. Here are my 2010 Asia predictions in retrospect:

1. There will be some kind of power-sharing deal in Iran before the end of the year.

X!

I really blew this one. My sense 12 months ago was that Iran was really slipping toward some sort of genuinely systemic crisis. Not primarily because of the street demonstrations. Those are relatively easy for dictatorships to contain with nasty head-crackings. In the movies (Avatar), the people overthrow the powerful, but in reality it is usually other powerful who overthrow the powerful. That is, elites usually depose other elites in dictatorships. And that is what I thought we saw in late 2009: the emergence of real splits inside the regime’s elites. Particularly, I thought that the clerics’ growing hesitation on Ahmadinejad’s policy of confrontation with the West might lead to a real cleavage requiring some kind of accommodation. Note that I did not predict a revolution or major change in the regime’s Islamist character. No one really expected that. But I did think that Ahmadinejad needed the clerics for legitimacy in what is still an overtly theocratic state. Looking back, I am fairly impressed at his ability to maneuver these domestic difficult waters, while nonetheless continuing to bluff the West. Yet perhaps the external bluff is the key to that internal success. Perhaps the nuke program insulates him against clerical unhappiness. He can appeal to a Persian populist nationalism with the nuclear issue, which allows him to ideologically outflank the clerics. If this is so, then Ahmadinejad is more enduring then we anticipate.

2. Israel will not bomb Iran.

✔

This is a negative prediction, so it was a little easier. But still, given how much noise Netanyahu and the Israel lobby in the US make on this issue, including regular veiled threats to take matters into their own hands, I do think this deserves some credit. Also, the Wikileaks revelations that Sunni Arab states might look that other way on a bombing add further weight to my prediction’s riskiness. Netanyahu is playing a tough negotiating game with the US, but this one was probably a bridge too far, although I bet the righties in his cabinet are unhappy. Still, Israel really needs the US, and that need will deepen the more it becomes apparent that the Israeli right is the primary force blocking an Israeli accommodation with the rest of the Middle East. And without US approval, unlikely on Obama’s watch, I still think the cost-benefit calculus tilts against an Israeli strike. That said, a strike is more likely this year, because the Iranian nuclear program keeps rolling along and Iran (point 1 above) has not softened.

3. Japan will disappoint everyone in Asia by doing more of the same – more moral confusion over WWII guilt and wasteful government spending that does nothing meaningful to reverse its decline.

✔

This is another negative prediction, and seems like an easy one too, because it just predicts more of the same from a country that has been doing that for 20 years. But placed the context of the DPJ’s (pseudo-)revolutionary election victory of late 2009, it still seemed like a mildly risky prediction at the time. Recall that the DPJ came in saying it would change so much – fixing the ever-sliding economy, improving Japan’s relations with its neighbors, edging away from the US, etc. All that turned out for naught. Some of this was because China seemed to flip out in 2010 (a big positive prediction I really missed – X!). China’s 2010 behavior pushed Japan back toward the US in a way the DPJ probably wanted to avoid. But on the other issues, Japan still strikes me as stuck in a terrible historical funk. It can’t seem to get beyond the fact that the glory days of its developmentalist economy (1960s-80s) are over, and that more Asian-style state intervention now just means more debt. Nor can it seem to figure out, despite the DPJ talk, that the rest of Asia is genuinely freaked out by Japan and pays attention to every change in Japan’s defense policy or utterance by defense officials. Worse, every time some disgruntled righty in Japan say the old empire wasn’t so bad after all, the neighbors go into paroxysms on incipient Japanese re-militarization. My own experience with Japanese students tells me that Japanese are just blind to this (although Japanese academics do seem aware). So my sense was that for all the DPJ talk, there was no real popular interest in a Willy Brandt-style ostpolitik on the history issues. Nor does that seem to have changed in the last year.

4. North Korea won’t change at all.

X! – It got worse!

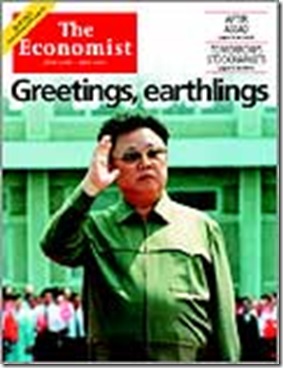

Who would have thought that the worst state in the world could plumb the depths yet further? Somehow the loopy Corleones of Korea – the Kim family gangster-state – became ever more unhinged and dangerous. My original prediction was aimed at those who thought that Kim Jong Il’s trips to China and China’s growing ‘investment’ in NK might somehow hail a Chinese-style liberalization, at least of the economy a little. To be fair, no one expected NK to morph into a ‘normal,’ somewhat well-behaved dictatorship like Syria or Burma. But there was a mild hope that NK, finally, under the weight of economic collapse and the pressure to show results for the 2010 65th anniversary of the state’s founding, might open a little. I thought that was far-fetched, so in that sense, my prediction was right. But more importantly, I missed that NK would actually go the other way. Instead of possible better behavior, NK went overboard – provoking three major crisis – the Cheonan, the new uranium plant, and Yeonpyeong– in just 7 months. Wow. Wth is going up on there?!

5. The US drawdown from Iraq will be softened, hedged and qualified to be a lot smaller than Obama seemed to promise.

✔/X

This one seems mixed but broadly accurate. It was a gutsier positive prediction, but the evidence is not definitive. I was genuinely surprised when the last brigades rolled out, but then, there are still 50k US troops in Iraq (more than in Korea or Japan, btw). Now that Iraq is off the front pages, and with Obama’s speech that it is all over, no one pays attention much. But we are still running around performing what really should be called combat operations, and Americans are still dying. And in Afghanistan, the Obama people are now openly moving the goal posts from 2011 to 2014 now. While I didn’t predict that, it does fit into my general sense that Obama can’t really end the GWoT quickly as he hinted during the campaign. Instead, it seems likely that it will slowly splutter out.